After spending half his lifetime building the family snack food company in the eastern Chinese city of Hangzhou, Yao Weizhong had run out of steam. His 22-year-old son showed little interest in the business, and Yao needed fresh capital and expertise to keep it growing.

So Yao, 48, chose a path taken by a growing number of Chinese entrepreneurs these days: He sold a controlling stake in his company, Yaotaitai, to a private equity firm.

“The company is hitting a bottleneck,” Yao, who sold the stake in December to Shanghai-based Lunar Capital Ltd., said last week by phone. “I don’t have enough energy at this age, and my kid is reluctant to take over. I can’t force him to like it.”

From the financial hub of Shanghai to the northern coal-rich Shanxi province, Chinese entrepreneurs facing the twin challenges of succession and a slowing economy are becoming more willing to cede majority ownership to buyout firms. It’s a tectonic shift in a market where the likes of Carlyle Group LP and KKR & Co. have traditionally been forced to forgo controlling stakes in order to enjoy the spoils of China’s breakneck growth, ever since the country opened up to private equity firms in 1994.

Overhauling Companies

Buying control will allow buyout firms to apply the model they’ve honed over decades in developed markets: Acquire undervalued companies and turn them around by cutting costs, replacing management and overhauling their strategies — unencumbered by resistance from entrenched founders.

“It’s indisputable that the control approach in China works better and returns more,” said Derek Sulger, a partner at Lunar Capital. He said it’s still hard to find large deals, especially in hot sectors such as technology and education, so private equity firms are focused on transactions involving smaller companies in the consumer and retail industries.

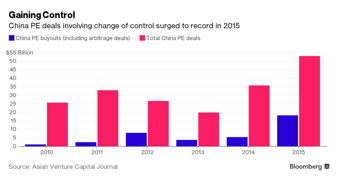

Deals involving a change of control accounted for 34 percent of the total value of private-equity transactions in China last year, more than double the share in 2014, according to Asian Venture Capital Journal. Excluding so-called arbitrage deals, which typically involve delisting companies and taking them public in markets where multiples are higher, “control” deals jumped to a record $6.8 billion last year from $4.9 billion in 2014, the private equity research firm estimates. That’s still just 13 percent of the total deal value.

Unhappy Offspring

Sulger said he is holding buyout talks with at least 10 Chinese companies whose founders or managers are looking to retire and sell controlling stakes. Among them is a snack-food maker in the Shanxi province whose founder’s son went to university in Canada, did a stint at an investment bank in Hong Kong and is now working at one of the large accounting firms in the city.

Derek Sulger | Source: Lunar Capital Management

“How can you expect the kid who left China during adolescence, grew up in Richmond in Vancouver, and then went to the University of Toronto, and then came back to run the family business in a rural part of Shanxi, to be happy?,” Sulger said. “These founders are very proud people” who want to see their companies continue to prosper even if their children don’t want to take over, he said.

“What they are really looking for is a solution to the succession problem that they know they are going to face,” said Sulger.

‘Sunset Industries’

Citic Capital Holdings Ltd. is in discussions with a 20-year old textile company which dyes cloth and exports mainly to the Middle East, said Eric Xin, a partner at the private equity firm in Hong Kong. With the business squeezed by a combination of falling sales, rising labor costs and the yuan’s appreciation in recent years, the 46-year old owner wants to sell out completely and move to the U.K., where he plans to educate one of his sons.

“It’s an industrial company in a polluted industry,” said Xin. “The kids don’t want to be in these sunset industries. They want to be bankers and financiers.”

In many cases it’s purely economic factors that are pushing China’s entrepreneurs to sell out. Citic Capital bought control of King Koil Shanghai Sleep System Co., a mattress maker, in 2014. When Citic was first introduced to the company in late 2013, its biggest shareholder wasn’t seeking an outright sale, Xin said. Six months later, as sales to the hotel business deteriorated, stocks piled up and profit margins eroded, the owner changed his mind.

Sulger of Lunar Capital said he’s hunting for fundamentally sound companies that are facing challenges that can be resolved with professional management. Chinese snack food companies, for example, typically have net profit margins of 4 percent to 6 percent, roughly half of what overseas competitors boast, Sulger said.

Paying Less

In the early years after China opened up to buyout firms, they had to pay more in the rare instances when they were able to gain control. As more companies have become available, the median enterprise value of deals involving a change of ownership has dropped to 7.2 times trailing 12-month earnings, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, from 11.6 times in 2014 and more than 17 times in 2013.

Business owners are getting more willing to acknowledge that they need help from private equity in weathering the slowdown and developing new skills in areas such as marketing, branding and research and development, Sulger said.

Many small business owners have never had to deal with the need to cut costs or implement sweeping changes, said Weiwen Han, co-head of Bain & Co.’s private equity practice for Greater China. “It’s about cost reduction, operational efficiency, changing the business model and transforming themselves. They’ve never done it.”

Conversely, many buyout firms haven’t developed the skills required to take over and overhaul Chinese companies, compared with the more passive role they’re used to playing. “They also need to invest in their own capability, to really understand how a mid-sized private founder-led business operates,” Han said.

Spiritual Pursuits

In Hangzhou, Yao said his decision to sell control of Yaotaitai, for an undisclosed sum, allowed him to focus on areas he is good at — such as where to buy the nuts, preserved fruits and additives that go in to the products. Among the changes Lunar Capital brought is an e-commerce platform, which Sulger said could generate as much as 20 percent of sales in the future.

Yaotaitai’s Chinese poultry snack. | Source: Hangzhou Yaotaitai Foodstuff Co.

For some of China’s entrepreneurs, the primary motivation for selling out is their own quest for a quieter life. Sulger said he’s talking to two companies whose owners want to retire and focus on spiritual pursuits, such as Buddhism.

“Because China is a little slower now, you have to run businesses smarter. You have to focus more on things like cost and e-commerce,” he said. “There is an enormous lifestyle issue emerging in China. A lot of these founders want to live and work in Vancouver, lots of them want to devote their life to other things like Buddhism, and lots want to simply retire.”

—

Access the original article here – http://mobile.bbwc.cn/article/10065254/1/cat_20?articleToken=ptnu2o